|

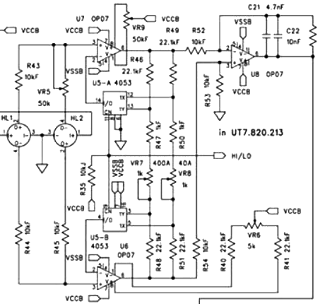

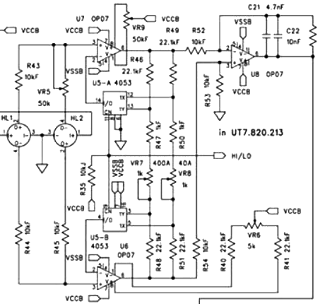

Here's an excerpt from the circuit

diagram, showing the two Hall sensors

HL1 and HL2 (the round things on the left) and their related

conditioning electronics. The output of the U8 op-amp (top right,

wired as a differential amplifier) is the analog signal of interest.

The range switching is handled by two sections of U5 (the

boxy things), which is a CMOS 4053 (triple

2-channel analog mux) in the feedback path of op-amps U6 and

U7 (output amplifiers for the two Hall sensors), and chooses

between two sets of feedback resistors (whose values in the schematic are

wrong, by the way—both the 40 A and the 400 A ranges

seem to have identical feedback resistor networks, which obviously

can't be correct).

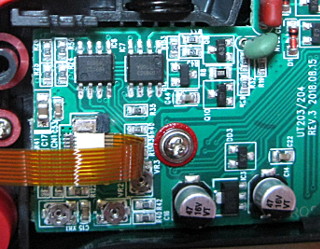

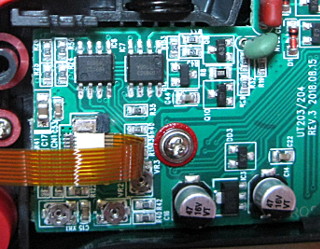

However, I hit an unexpected snag when I opened up my UT203—mine

seems to be a newer revision, with a different circuit. The PCB on mine

is labeled "UT203/204 REV.3 2018.08.15", and at the very

least it:

- has different op-amps (two GS8552 rail-to-rail low-voltage

dual op-amps, whereas the schematic has OP07 single

op-amps)

- has no 4053 (unless it's on the reverse side of the board,

which I did not remove for inspection)

- has a 24LC04B eeprom chip, for whatever reason (factory

calibration data, I'd guess)

- seems to have a different central IC as well, at least based on its

pin count.

Nevertheless, I think the analog front end of the Hall sensor read-out

circuit must be essentially the same as what is shown in the schematic.

I just need to find the correct pin on the correct op-amp to get the

output signal I want.

|

|

So I looked up the

datasheet for

the GS8552, and armed with its

pinout, I switched the instrument on and began probing the two op-amps

IC6 and IC7 with a multimeter, measuring against the COM

terminal of the UT203 (which was just a lucky guess as to what

might serve as "ground"). I first measured the supply voltages.

Then I measured each output pin with zero current, +4 A current, and

−4 A current passing through the clamp. (At this time I paid

no attention to whether the wire is properly centered and perpendicular

to the clamp, as it should be for accurate results.) I observed that:

- on either amps range, both op-amps are fed with +1.95 V (Vdd)

and −1.09 V (Vss). The battery

terminals, at the same time, measure +7.99 V and

−1.09 V relative to COM.

- on the volts and ohms ranges, the op-amps are still powered,

being fed with +1.11 V and −1.82 V, whereas the battery

terminals are +7.51 V and −1.82 V.

- on the Hz range, battery negative measures −1.46 V, and

on the diode test range −0.37 V.

- on the 40 A range, the outputs A and B (pins 1

and 7) of IC6 and IC7 measured:

| No current |

+4 A current |

−4 A current |

| IC6 output A |

−164 mV | −176 mV |

−155 mV |

| IC6 output B |

−164 mV | −155 mV |

−172 mV |

| IC7 output A |

+263 mV | +262 mV |

+264 mV |

| IC7 output B |

−2 mV | +21 mV |

−18 mV |

So it seems like COM is at a virtual ground that is adjusted

differently for different measurement ranges. On the amps ranges it

is some 1.09 V above the battery negative terminal, and on other

ranges within reasonable (and safe) limits not to wreak havoc with any

op-amp I choose to use. The two op-amp

ICs seem to be powered through a 3 V regulator, likely IC3

which is marked "SD30L".

The two halves of IC6

seem to do the job of op-amps U6 and U7 in the old

schematic, i.e. they amplify the Hall sensors' outputs—note

how they act as "mirror images" of each other with positive

and negative current through the clamp. The

"B" half of IC7 seems to be the differential

amplifier (U8 in the old schematic) and its output is the analog

signal that's proportional to the measured current. Its output

is very close to 0 V at zero current, which confirms that the

COM terminal is indeed at the correct virtual ground here. The

"A" half of IC7 is probably the constant-current

supply for the Hall sensors, as it never changes at all.

|

|

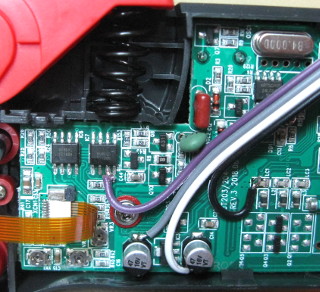

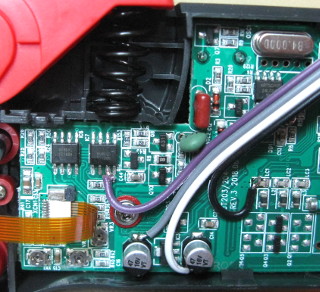

To connect my own circuit to the instrument, I needed access not only to the

analog signal from IC7, but also to the virtual ground, and

on/off-switched power supply voltages (VccB and VssB in the old schematic).

I did not want to remove the

circuit board in order not to disturb the connections to the buttons and

LCD (sometimes reassembly can be a pain, so I try to minimize disassembly).

Therefore I chose locations that are easily accessible to the soldering

iron on the front side of the PCB:

| VccB | positive leg of C16 (gray) |

| VssB | negative leg of C14 (white) |

| GND | upper end of LC1 (black) |

| Signal | pin 7 of IC7

(purple) |

I breadboarded a circuit using an

LM358 op-amp and started testing. I chose the LM358 just

because I happened to have it immediately

available in shelf. It is unity-gain stable, and its input and output

voltage ranges go within

20 mV of the negative rail, so it will work just fine with a

virtual ground 1.09 V above negative rail. The positive end of its

output range is more limited, some 2 V below the positive rail,

but that's ok as I'm

using the unregulated battery voltage, not the regulated 3 V, as the

LM358's positive rail. The output range (which needs to be symmetric)

is, of course, limited by the negative supply to ±1 V, but

if I aim for 10 mV/A sensitivity (the same as on the

Fluke i310S), the full-scale output will be just

±0.4 V, which is ok.

|

|

With wires soldered so I don't have to hand-hold the multimeter probe,

I was able to more carefully measure the analog voltage with respect to

current, this time with the wire properly positioned in the current clamp's

jaw (not that it seems to matter much). The analog signal from IC7

turns out to be 6.53 mV/A on the 40 A range, and 0.638 mV/A

on the 400 A range. (Rather strange values, but if the

instrument is factory calibrated into the eeprom chip, the exact magnitude

of the analog signal doesn't really matter. However, if you do the same

modification on your own instrument, you'll likely get different values, and

will need a different gain—probably the gain potentiometer in my circuit

will accommodate it, though.)

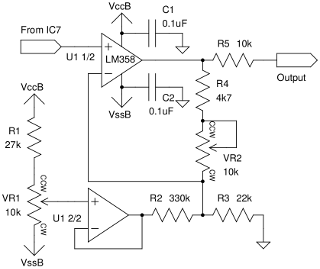

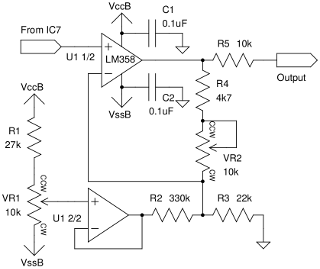

The output circuit I designed could

hardly be simpler—it is just a non-inverting amplifier (with

gain that can be set with trimmer VR2 from about 1.2× to

1.7× to get the desired 10 mV/A sensitivity) with an offset

control. Note that the analog output's offset is not affected by the

instrument's own zeroing function, and likewise the digital readout is

unaffected by the offset potentiometer—the two are completely

independent. The voltage from the divider formed by R1 and

VR1 is about ±1 V relative to the virtual ground. That

becomes about ±60 mV in the following voltage divider formed by

R2 and R3. The impedance of that divider is about

20.6 kΩ,

and together with R4 and VR2, the feedback network gives the

upper half of op-amp U1 the desired gain range. Note that the input

signal connects to the op-amp positive input only—that input is

high-impedance, so my circuit does not load the signal in any significant

way, and should therefore not affect

the internal workings of the UT203 at all. Also, since no feedback

resistors connect to the input signal, there's no way that my circuit,

which runs off a higher voltage, could damage the low-voltage IC7.

Since the offset voltage is derived directly from

the unregulated battery voltage, it will drift slightly as the battery

wears down, but that's not really a big deal compared to other drifting

in a cheap instrument like this.

The output impedance of my circuit is 10 kΩ, which is high enough to

make an inadvertent short-circuit a non-issue, yet low enough not to skew

the voltage at an oscilloscope's input, which is typically around

1 MΩ.

|

|

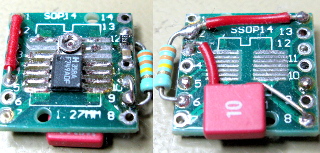

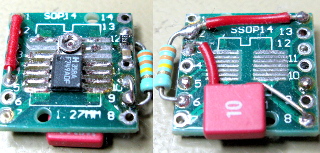

There's plenty of room inside the instrument's case otherwise, but the

populated circuit board cannot be very thick. A DIP op-amp on a scrap

of veroboard might just fit, but since I had SMD components

handy, I played it safe and used those as much as possible. I built the

circuit on a tiny 14-pin SOIC-to-DIP adapter PCB from eBay—the IC

and gain trimmer fit nicely on the SOIC pads, and the two capacitors and

five resistors, in either SMD or through-hole format, go between various

DIP pin holes. A custom PCB might look better, but with such a simple

circuit I just couldn't be bothered to fabricate one.

Here is a bigger photo of this mess.

|

|

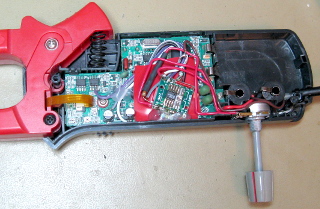

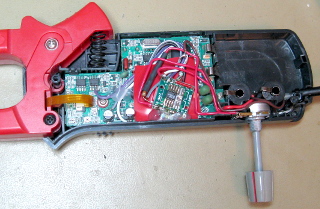

I stuck a couple of layers of electrical tape (bush-league though that is)

over a suitable part of the instrument's PCB for insulation, and wired up

my own PCB to sit there, with the trimmer (gain) potentiometer side facing

up. Some hot glue keeps it from wandering about. Once the instrument's

case is closed, it should be quite snug in there.

The offset adjustment potentiometer is located near the banana jacks,

where a small pot (4 mm shaft) will just fit after some

grinding, but this was the tightest and most awkward bit of the whole

modification. The output cable exits the instrument through a hole I

ground near the lanyard

attachment point, at the lower-right corner of the case. A cable tie

provides strain relief. The coax shield is connected to the virtual ground

at the COM jack. Click

here for a bigger photo.

I adjusted the gain potentiometer by feeding 10 A current through

the jaw (I looped a wire through it five times, centered it as carefully

as I could, and fed it 2 A from my power supply), while

monitoring the output on my oscilloscope. After that I reassembled the

instrument's case and cut the offset potentiometer's shaft to its final

length.

|

|

The thing works as intended, though it's quite sensitive to external

interference. Adding some copper tape inside the case, grounded to the

negative terminal of the battery, improved it somewhat. It still helps to

switch off the fluorescent ring light in my desk magnifier lamp when using

this with the oscilloscope, big deal. Or I can put multiple turns through

the jaw to get more signal, and scale the results accordingly. It's accurate

enough on the 40 A range (well, I calibrated it, didn't I), and the

400 A range doesn't seem to be too far off either.

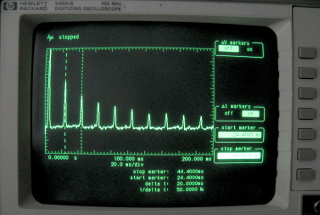

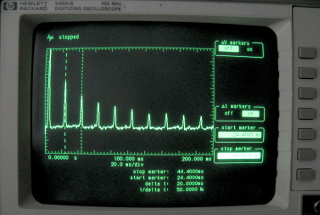

Here's an example oscilloscope

trace of the inrush current when switching on my 200 VA isolation

transformer. The first peak is some 120 mV, which would be 12 A,

but I had four turns through the jaw, so it comes to 3 A. The

peaks occur at 20 ms intervals (that's 50 Hz), and the peaks

are all either positive or negative, depending on the magnetization state

of the transformer's core when it was last switched off, i.e. during

which half-cycle of mains AC power. As there was no load connected, no

current flowed after the initial inrush.

|

|

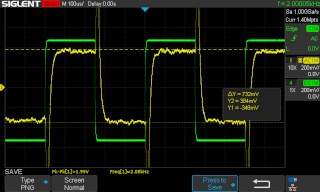

As these clamps are mostly used to measure things like household AC current,

I wouldn't be surprised if the instrument's bandwidth were just a few

hundred Hz. To gain some idea of the bandwidth, I fed an ordinary stereo

amplifier with a sinewave from my signal generator, and connected an

8 Ω power resistor to one of the speaker outputs. I then looped

the output wire through the clamp's jaw a couple of times, and increased

volume, while monitoring the output on my scope. I set the cursors at the

sine wave's peaks at 500 Hz, then started increasing the frequency.

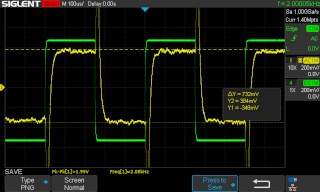

The output amplitude stayed very constant up until 2 kHz, but beyond

that it, surprisingly, began to increase. I switched to a

square wave, and saw this waveform

(the green trace is the input signal, the yellow trace is the current

clamp's output). Obviously something causes a tremendous high-frequency

response somewhere,

and I don't really know whether it's in the stereo amp or in the current

clamp. But at least up to 2 kHz the thing behaves very well.

|

I don't know if the same modification is

applicable to the

Of course, I take no responsibility for the correctness of the above

information, and if you decide to modify your own current clamp, you do so

entirely at your own risk. Let me know how it turns out.